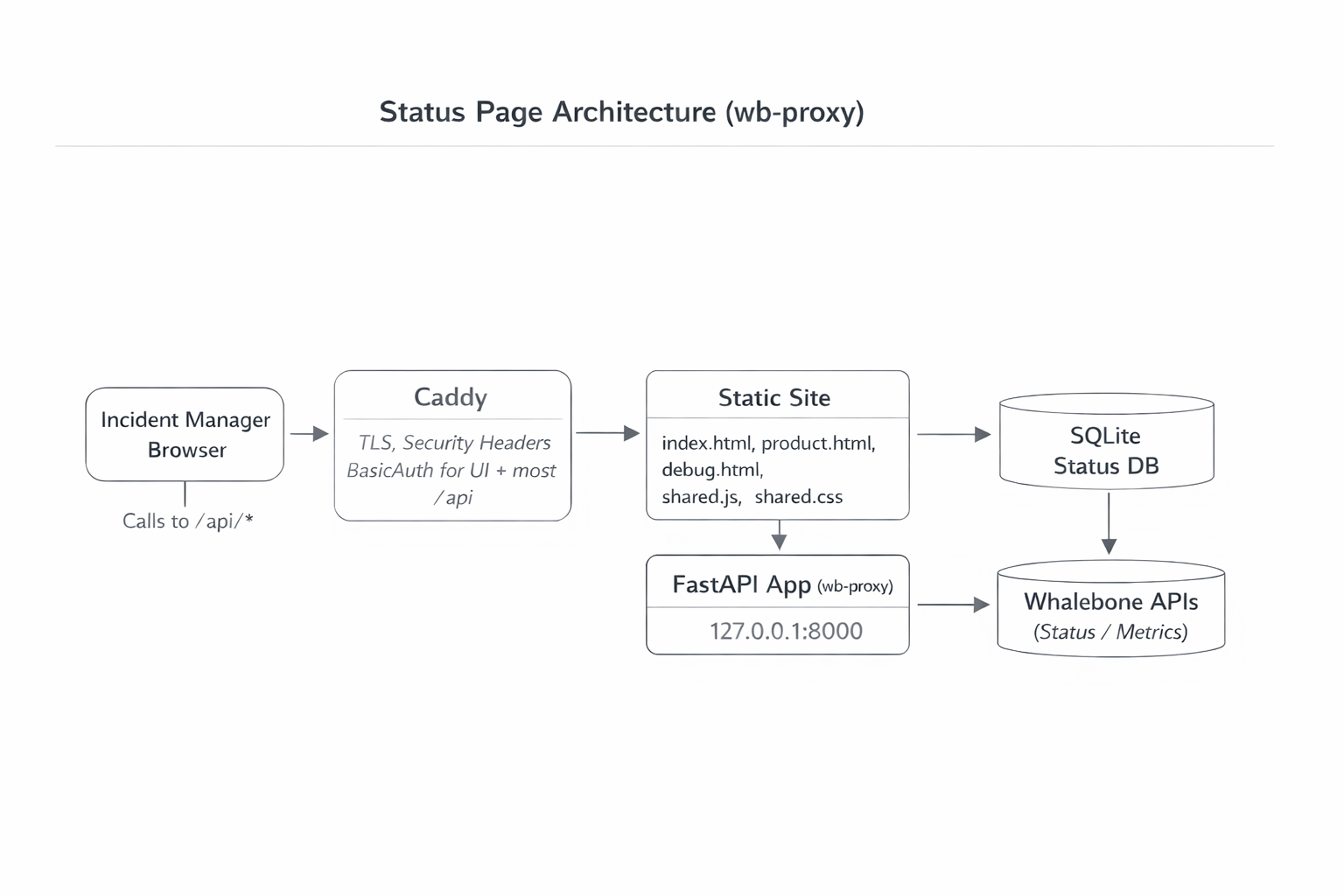

I built a simple status page for a test tenant with test resolvers so I can see real-time health and a lightweight history of degradation events.

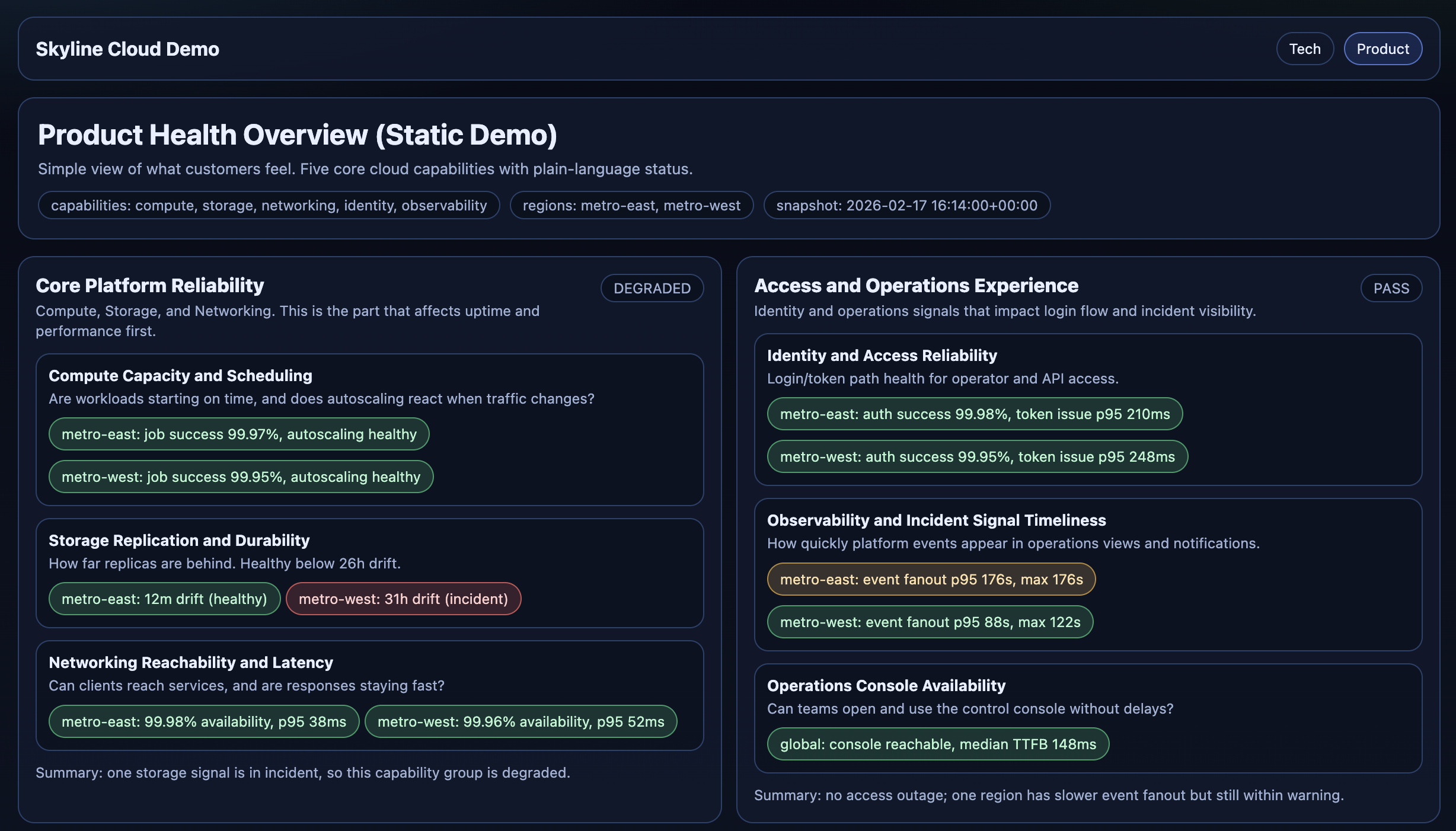

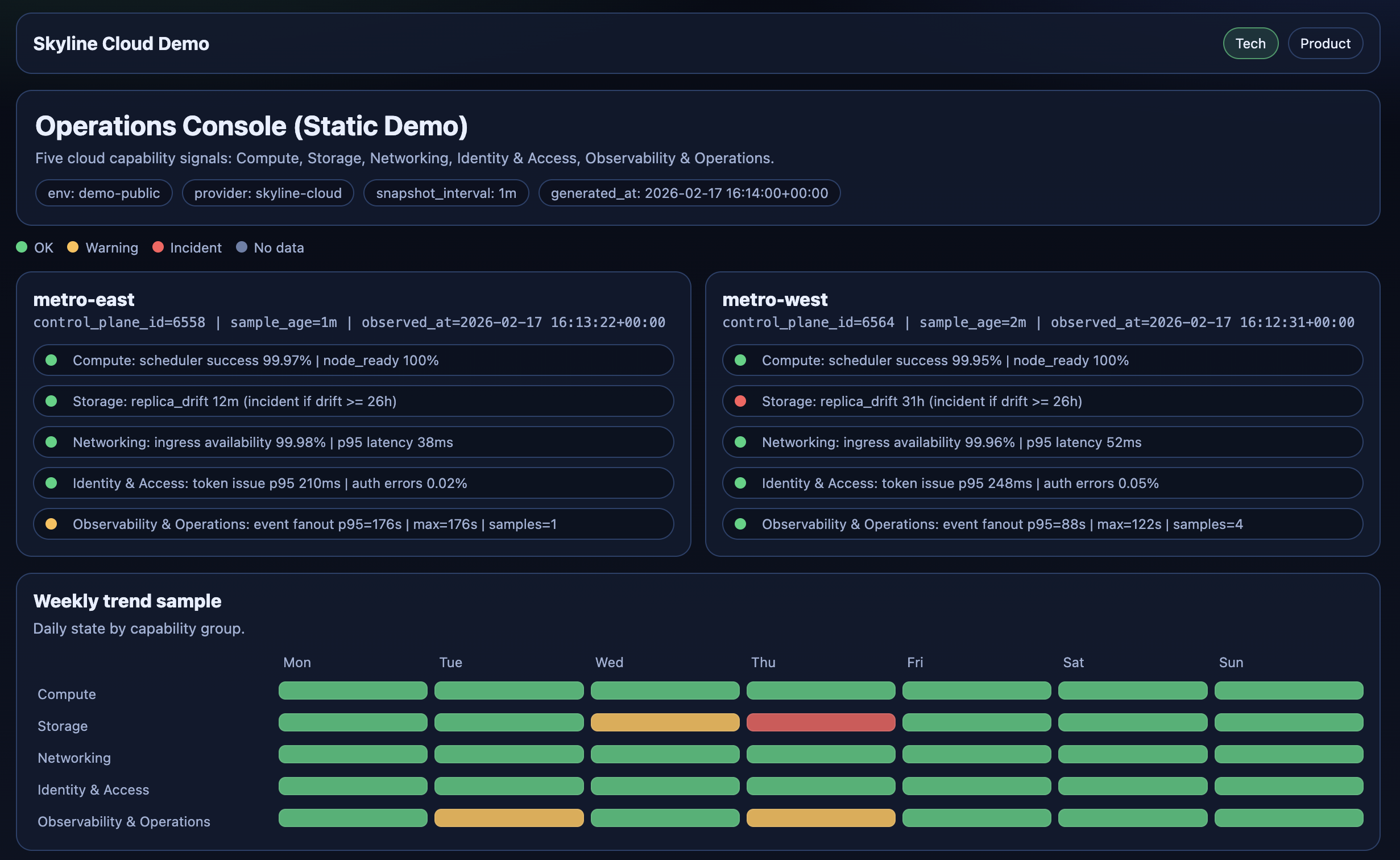

It’s not a customer-facing product. It’s an incident tool for me: one place to answer “what’s broken, where, since when?” before anyone else reports it.

It’s private and access-controlled, but it lives on a real server. I treat it like production anyway.

Why I Built This

Whalebone has a status page, but it’s updated manually based on alerts and internal reports. That’s fine for broad comms, but it’s not the same as having a single, always-on view tailored to the failures customers actually complain about.

So I started with a blunt rule: monitor what creates the most incidents and the most customer complaints. No debate, no perfect metrics taxonomy. Just signal first.

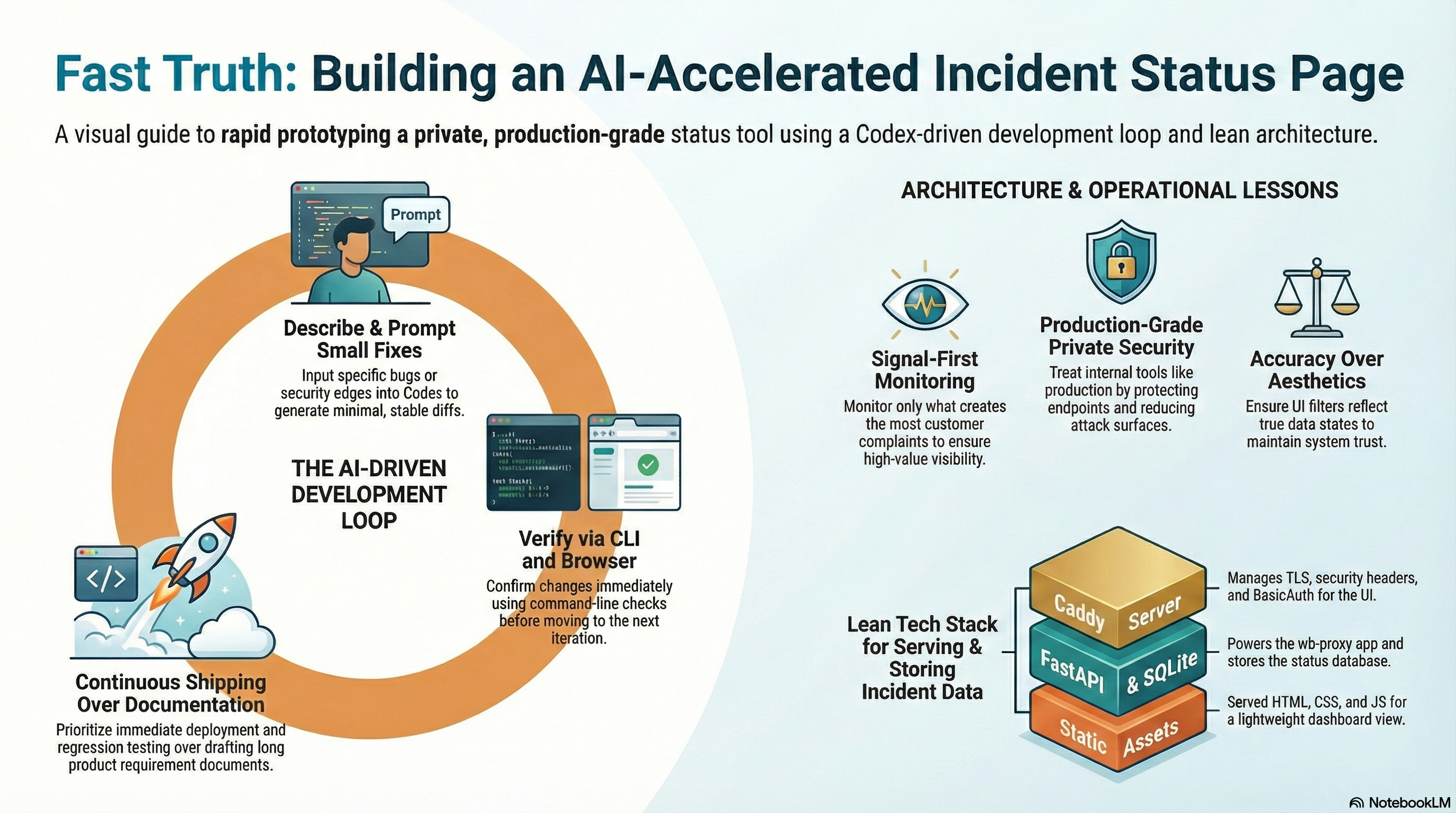

Why Codex, Why Now

I’m a Product Manager, and I used to be a backend developer. If I wasn’t doing this myself, my “default mode” would be: write a short spec, prioritize it, and hand it to the team.

But this was a prototype. I wanted something useful quickly, and I didn’t want to burn team time on it yet.

I’d already been using ChatGPT, but copy-pasting snippets into an editor is friction-heavy. Codex (GPT-5.3-Codex) let me work in a tighter loop: edit multiple files, add tests, commit, push, and iterate.

The Loop

- I described one specific problem (bug, deploy issue, naming, security edge).

- Codex made a small change.

- I did a quick diff review.

- I shipped it.

- I verified it in the browser and with a few command-line checks.

- I told Codex what to adjust, and repeated.

That loop is the real “feature”: rapid verification. Everything else is just output.

Incidents That Shaped the Project

1) “It’s Deployed” (It Wasn’t)

I pushed a deploy and the page opened, so at first it looked done. But something felt off: styling and behavior were broken in ways that looked like “bad JavaScript.” I only opened the browser console after that, copied the errors (missing assets, strict MIME type errors), and asked Codex to fix the root cause.

Instead of debugging UI code, I checked what the server was actually returning. The problem was not rendering logic. The problem was what got deployed versus what got served.

I changed the deployment model for static files so shipping only a single HTML file without shared assets became much harder.

If you ship static pages, deployment is part of correctness. “Merged” and “served” are different states.

2) Self-Hosted CI Runner Reality Check

The next issue looked unrelated: CI jobs either waited forever or failed fast with missing-module style errors, even though the self-hosted runner was “online.”

The useful signal was in workflow logs, runner labels, and job environment setup, not in the green “runner connected” status.

I tightened how tests execute and made runner setup more predictable.

A self-hosted runner is not a toy. Unless you isolate it properly, it shares a machine with real services and fails in operational ways, not just code ways.

3) A UI Bug That Was Really a Data Bug

Then I hit a bug that looked visual but was actually data logic: filtering “not wired” checks hid some modules, but mixed modules still showed unwired rows. The page felt inconsistent and hard to trust.

I traced it to where state was computed versus what rows were actually visible after filtering.

I moved filtering to feature-row level, computed module state from visible rows, and added a small regression test so it cannot silently return.

Status UIs fail when they lie by omission. Correct filtering is not cosmetic, it is part of accuracy.

Security: “Private Page” on a Public Internet

I learned this lesson the fun way earlier: I spun up a personal DNS resolver for my laptop and got hit by a DDoS quickly. That experience changed how I treat “small” services.

Even though this status page is “just for me,” it sits on a real server. So I treated it like production from day one: protect endpoints, reduce attack surface, and assume it will be poked.

What I Verify Before I Trust It

- Run tests before shipping changes.

- Verify what the server is actually serving (not what I think it serves).

- Validate and reload the web server config safely.

- Check permissions/paths for static files.

- Hard refresh the browser only after the above is clean.

How I Used Codex (Prompt Patterns)

The prompts that worked were boring and strict:

- “Fix this specific bug. Keep diffs small.”

- “Add a regression test for exactly this behavior.”

- “Give me a verification command that proves the deploy is correct.”

- “Rename this UI label to be product-readable (no technical jargon).”

- “Don’t refactor. Just make the change and keep behavior stable.”

What Success Means for Me

Right now the dashboard is mostly green. That’s fine.

Success is not “red graphs.” Success is earlier detection: I want to see a system drifting before customers feel it, and before anyone messages support or escalates internally.

That’s the whole point: one page, one glance, faster truth.